- Sumatra’s Kerinci Seblat National Park is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra (TRHS), which has been inscribed on UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger since 2011.

- UNESCO has noted particular concern about a spate of road projects planned for Kerinci Seblat and other protected areas within the TRHS.

- According to park officials, Indonesia’s forestry ministry has refused permits for all new roads within the park; the sole project to receive permission is the upgrade of an existing road.

- The park still faces immense pressure from encroachment for agriculture, logging, mining and poaching.

The rainforests that once carpeted Indonesia’s Sumatra Island are among the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems, home to iconic species like the Sumatran tiger, rhino and orangutan. They are also among the most imperiled; in just two decades, between 1990 and 2010, Sumatra lost 40 percent of its old-growth forest. The tigers, rhinos and orangutans that roamed those forests are now critically endangered.

Much of the intact forest that remains is protected, at least nominally, in a series of National Parks, and, since 2004, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra (TRHS).

In recent years, concern has grown that Indonesian authorities are not doing enough to protect this critical biodiversity hotspot. Since 2011, the site has been inscribed on UNESCO’s List of World Heritage In Danger due to the risks of logging, encroachment, road expansion and poaching.

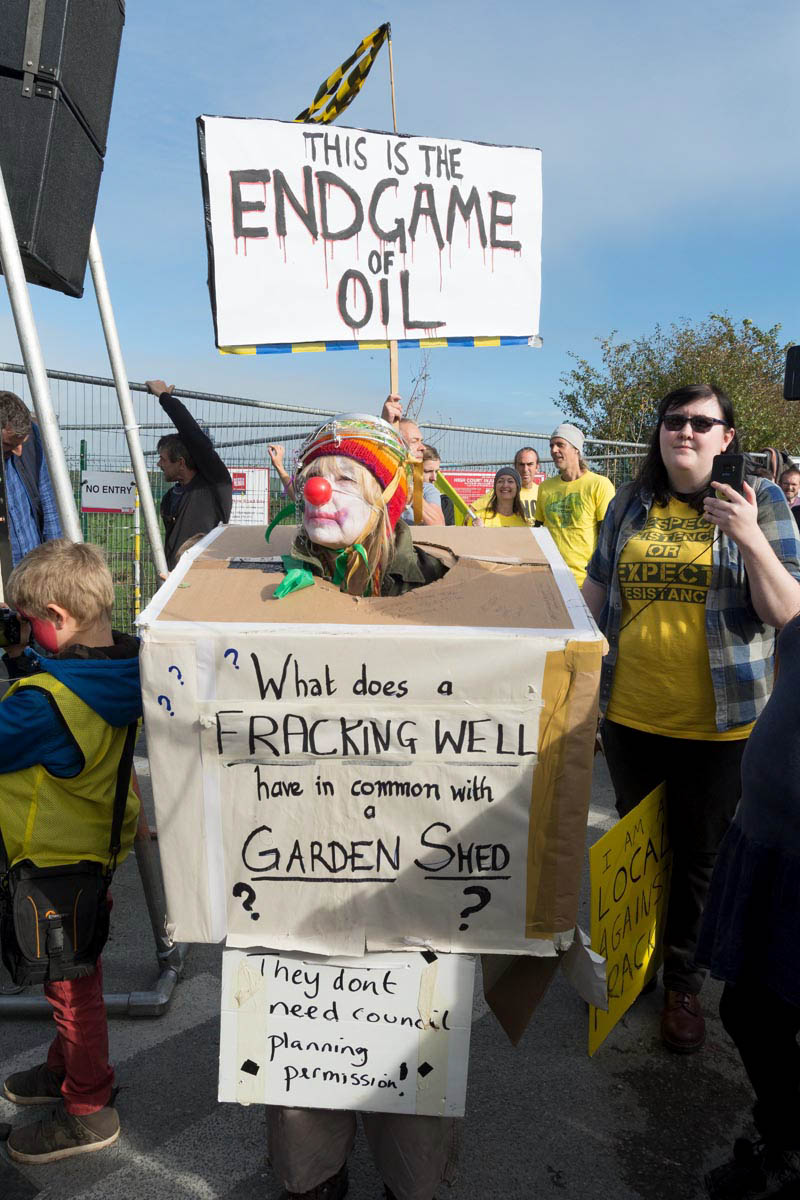

In 2016, UNESCO flagged up concerns about road construction in the area, particularly in Kerinci Seblat National Park, a protected area extending for 350 kilometers (217 miles) from northwest to southeast along the rugged spine of the Bukit Barisan Mountains.

In the years since, it’s been some good news and some bad news for Kerinci Seblat National Park.

Canceled Roads

In 2016, UNESCO identified 12 planned or proposed road projects in four zones of the park. Now, park officials say, the list of road expansion projects of concern has been whittled down to five. And of those, four are cancelled. The only project currently set to go forward is the improvement of an existing road, which runs from Sandaran Agung mountain across to Tapan near the West coast.

According to Hadinata Karyadi, a spokesman for Kerinci Seblat National Park in Sungai Penuh, the town encircled by the park, the local office of the forestry ministry had formally recommended to the minister that the four now-cancelled projects be denied approval. For example, Karyadi says his office urged the ministry to refuse approval for a proposed road through the village of Lempur because it threatened critical tiger habitat. Those rejections were duly issued over a two-year period, with the last project being denied a permit in 2018.

The road-improvement project that was approved presents fewer environmental concerns, Karyadi says, because it involves upgrading an already existing road rather than building a new one. The current road is steep, winding and currently in such bad condition that even public minibuses will not use it, Karyadi says. Once improved, though, he says the road will be sufficient to serve as an evacuation route in case of natural disasters — one of the frequent justifications for proposing new road projects in the park. “Improving the existing road is better than building a new one,” he says. “If it is good, it will be enough for evacuation needs for now.”

Some concerns do remain, because any increase in traffic on a road through the park could affect the local wildlife. In late 2018, Fauna & Flora International (FFI), an NGO working closely with the national park management, planned an “intensive biodiversity survey” to “assess impacts of upgrading a road running through the national park and make recommendations to government.”

For now, the most hazardous road proposals seem to be off the table, though FFI notes that “local political elites” continue to push for the revival of the cancelled projects. But the park and its ecosystems remain under serious threat due to population growth, agriculture and industry.

“Encroachment on the national park is the main problem,” Karyadi says. He adds that the current staff of around 70 rangers isn’t enough to police the huge perimeter and that his office has requested a larger budget.

A rejected road

One of the most controversial projects was the proposed new road in the south of the park, through Lempur. At present a trail runs from Lempur, through the village rice fields and continues as a wide rocky walking trail that winds through the forest. According to locals, it’s been there ever since anyone can remember. These days it’s used mainly to get to local tourist sites such as Kaco Lake and for trekking to the national park.

“My team made a full report and gave it to the ranger,” says trekking guide Andi Tiasanoawa in Lempur, explaining his response to the road proposal. “We don’t want people cutting the trees,” he says, adding that he makes his living from the forest and doesn’t want it damaged.

Guide Zacky Zaid, who has been trekking these hills regularly for 10 years, says a past road project in the area made people aware of the potential downsides such developments can bring. Zaid says that around five years ago the government agreed to build an access road to the village of Renah Kemumu inside the park boundary. “This route was one of the popular five-day treks that we did,” Zaid says. But once the road was built, the wildlife that the tourists came to see dwindled. “Lots of people cut the trees when the government built the road,” he says. “The nature is not really good anymore. There are no big trees anymore. For us I’m so sad. We closed trip there a couple of years ago.”

Ultimately, the Lempur road was rejected “because it threatened the tiger core area,” Karyadi says.

Fertile farming

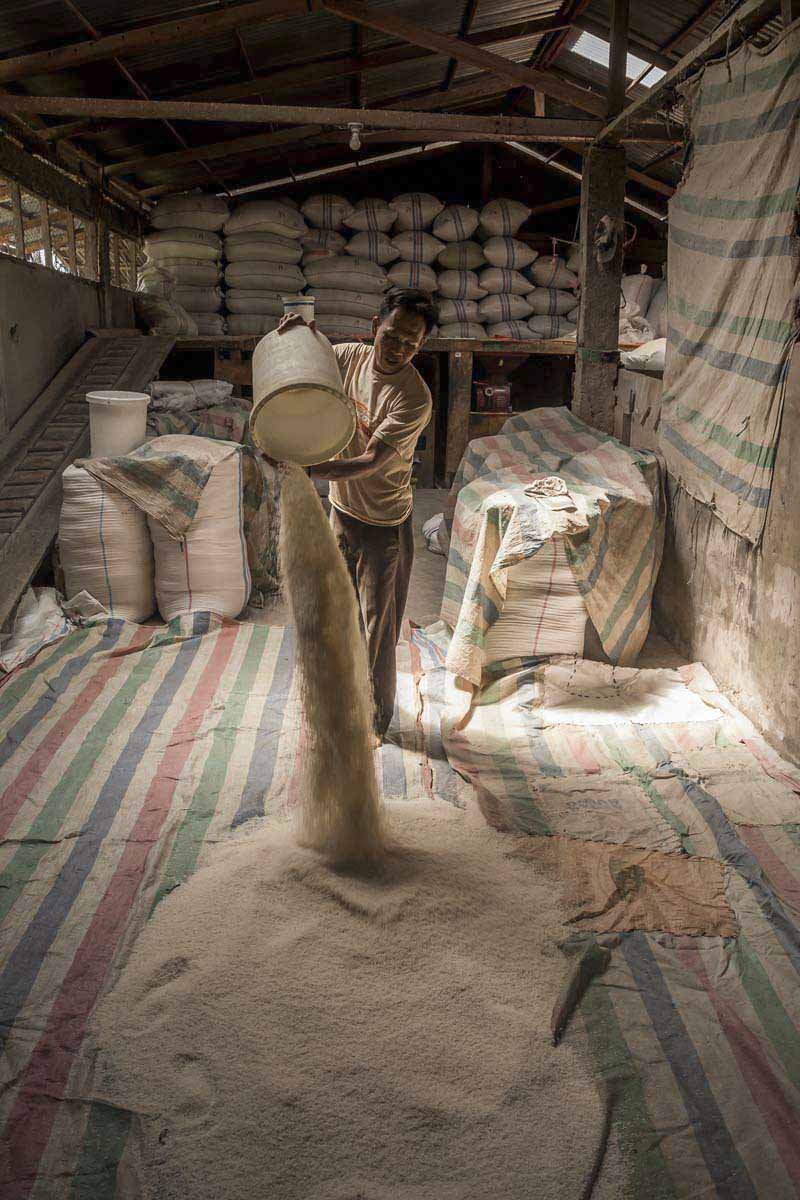

At 3,805 meters (12,483 feet) above sea level, Mount Kerinci is the tallest volcano in Indonesia, and dominates the landscape here. The alluvial sediment deposited by past eruptions provides the valley with mineral-rich soil that draws farmers. Steep hills that ring the valley create the boundary to the national park beyond. Migration into the valley has led to pressure on the park as farmers encroach on the hills.

A huge 10,000-hectare (24,700-acre) tea plantation stretches across the valley floor; in between, farmer’s plots host a variety of everything from potatoes to tomatoes and coffee.

As the elevation rises and the valley floor gives way to the steep mountain slopes, the crops change to cinnamon, rubber, coffee and cloves. These tree crops give the slopes a forested appearance, but close up the hills are cultivated and densely populated with farming communities.

“The cinnamon boom is a particular problem” driving encroachment, says Karyadi. Others see it as a benign and sustainable traditional practice that also has economic benefits for poor farmers.

In the farming village of Talang Kemulun at the foot of the hills that form the valley’s southern perimeter, Eibru Hajar says he mainly grows cinnamon and coffee on his own land. “I have around a hundred cinnamon trees and cut them in a rotation cycle of 15 years,” he says. “I get around 50 kilos [110 pounds] per tree.

“The rangers come by every couple of months,” Hajar adds. “So I’m afraid of cutting the trees [inside the park boundary]. The penalty for cutting forest trees is a big fine and if you don’t have money you get several months in prison.”

But the threat of penalties doesn’t deter everybody, and NGOs like FFI report that land continues to be cleared within the borders of the park.

Illegal mining is another threat. In a 2018 report, FFI said it found alluvial gold mining sites in and around the park’s borders, “posing serious threat to a key tiger corridor with a dirt road constructed which entered the edge of the national park.” Despite the central government’s commitment to protecting the park, local political pressure on the park remains high. In 2017, it spilled into open conflict when gold miners held a municipal government official hostage, according to FFI.

FFI also tracks illegal logging and poaching of pangolins, tigers and other wildlife. It notes that law enforcement efforts since 2016 did seem to have an impact on reducing the poaching, but that these efforts remain a challenge.

With agribusiness and extractive industries hungry for new land, the pressure on Sumatra’s forests is relentless. Kerinci Seblat is no exception, and migrant farmers have swelled the local population, placing further pressure on the national park.

Last year the park management set up a Role Model Program, to try and stem escalating encroachment, especially by migrant farmers who frequently claim that the park’s boundaries are unclear.

“The park boundary is well demarcated with concrete markers about one meter [3 feet] tall,” Karyadi says. “In some places locals have dug up the marker posts.”

The scheme aims to restore encroached forest and establish alternative livelihoods. Along the way are manifold obstacles, not least gaining the participation and cooperation of sometimes reluctant farmers.

“This week we caught some illegal loggers and handed them to the police. They will be judged by the law,” Karyadi says. His office is trying to navigate a tricky path between encouraging farmers to change their practices through incentives (some get financial rewards under the Role Model scheme), and punishing offenders who have clearly broken national park rules.

For now, encroachment by farmers is ongoing, but local political attempts to accelerate this by opening up new areas through road-building have been limited. Meanwhile, political tensions remain between politicians seeking more infrastructure building and the forestry ministry, which works with the support of international NGOs to maintain the integrity of the national park and its borders.

This article was first published by mongabay.com